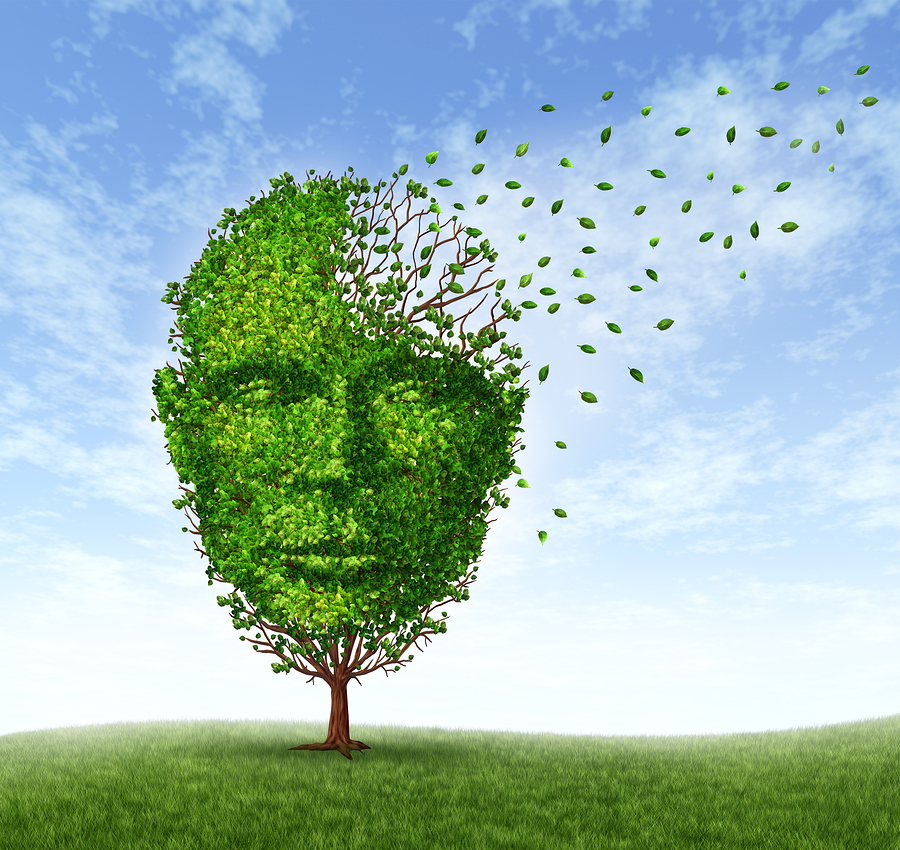

Many people around the world have loved ones affected by dementia, a disease that is marked by memory disorders, personality changes, and impaired reasoning. Perhaps no country has experienced the dramatic effects more than Japan. Last year, more than 10,700 Japanese residents with dementia were reported missing. Often times, this is due to the wandering off that comes as a symptom of memory loss, an effect of dementia.

Japan has more than 10 million citizens over the age of 80, making their country one of the highest in life expectancy. Additionally, one-fourth of Japan’s population is over the age of 65. There are already 5.2 million Japanese over 65 with dementia. That will rise to up to 7.3 million in 2025—roughly one in five of Japan’s elderly people, and one in 17 of its total population. As well as wandering about aimlessly, dementia sufferers have a tendency to become confused by changes in their environment, and lash out verbally (Quartz).

Dementia is paralleled by the nation’s birth rate reaching all-time lows. The low birth rate is partially due to the now-working class preferring career life over family life, a major difference from 50 years ago. Coupled together, these are sure to cause Japan’s population to decrease dramatically by 2040.

Last year, it is reported that nearly 440,000 workers left their jobs in order to care for family members with the disease. With a working class that is shrinking, this is not good news.

Japan may be the perfect population to test the disease in. Other countries around the world have growing life expectancies that will soon look like Japan’s. In fact, in South Korea, Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain, more than 40% of the population will likely be over 60 years old in 2050. How Japan copes with dementia may provide some much-needed lessons for the rest of the world. Here are just a few of the things Japan is trying.

Long-term care insurance. Under this mandatory system, rolled out in 2000, at age 40 every Japanese resident pays a monthly insurance premium. They become eligible for a range of services—including daycare centers and meal delivery—when they turn 65, or get sick with an aging-related disease. The idea is to help seniors live more independently, reduce the burden on family caregivers, and create a market of companies competing to provide the eligible services.

Dementia-care training. The government initiated dementia training programs for physicians and nurses and hopes to have 87,000 people participating in them by the end of 2017.

Short-term-stay offerings. Family members who care for those affected with the disease may seem distraught or tired at times with everything that goes into the care needed. This option can be used for an occasional break, bringing in relatives for stays of up to 30 nights.

Search-and-rescue programs. Being tested in about 40 cities, these efforts involve teams of social workers and medical professionals looking for people who have dementia but have not yet been diagnosed with it. The teams attempt to sign people up for services offered under the long-term care insurance program. Japan hopes to have teams in every city in a few years.

Cooperation with stores. Four major convenience store chains agreed to function as “dementia supporters” to assist seniors who appear disoriented. The chains, which between them have about 3,500 stores, send store managers to training sessions on how to identify and assist dementia sufferers. [A few solutions]

We hope to learn a great deal of information about the disease and how to treat it. It will not just go away on its own and perhaps Japan may soon have the answers.